Physical anthropologists working in the Dutch East Indies used blood samples, physical measurements, and the human remains of indigenous people to promulgate racial categories. The undeclared motivation for doing so was likely to establish alterity between the autochthonous people of Indonesia and members of the Dutch State, as well as its European allies in order to apply eugenic ideologies in an effort to maintain the power and authority of the Dutch Colonial Regime.

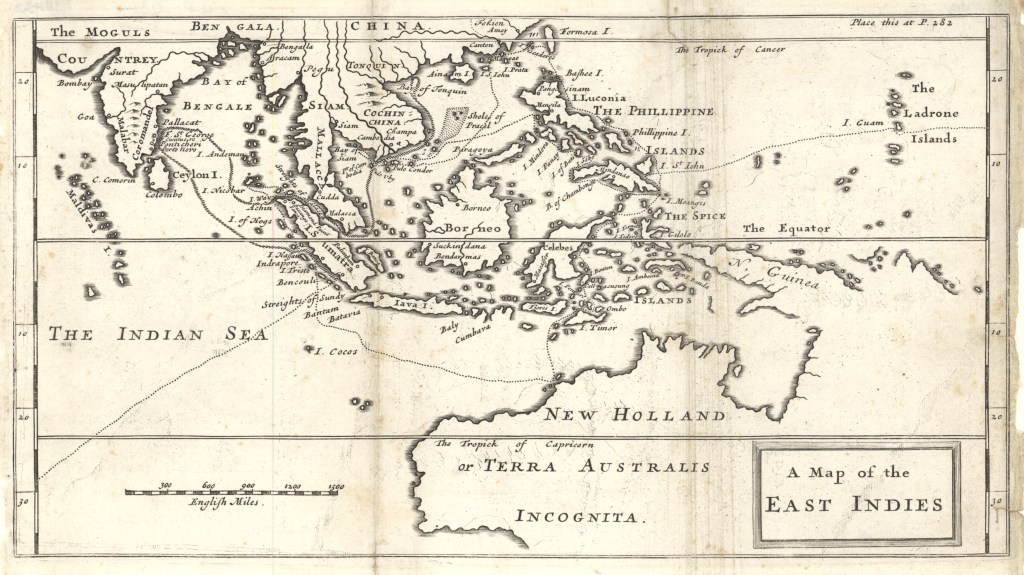

The Dutch East Indies

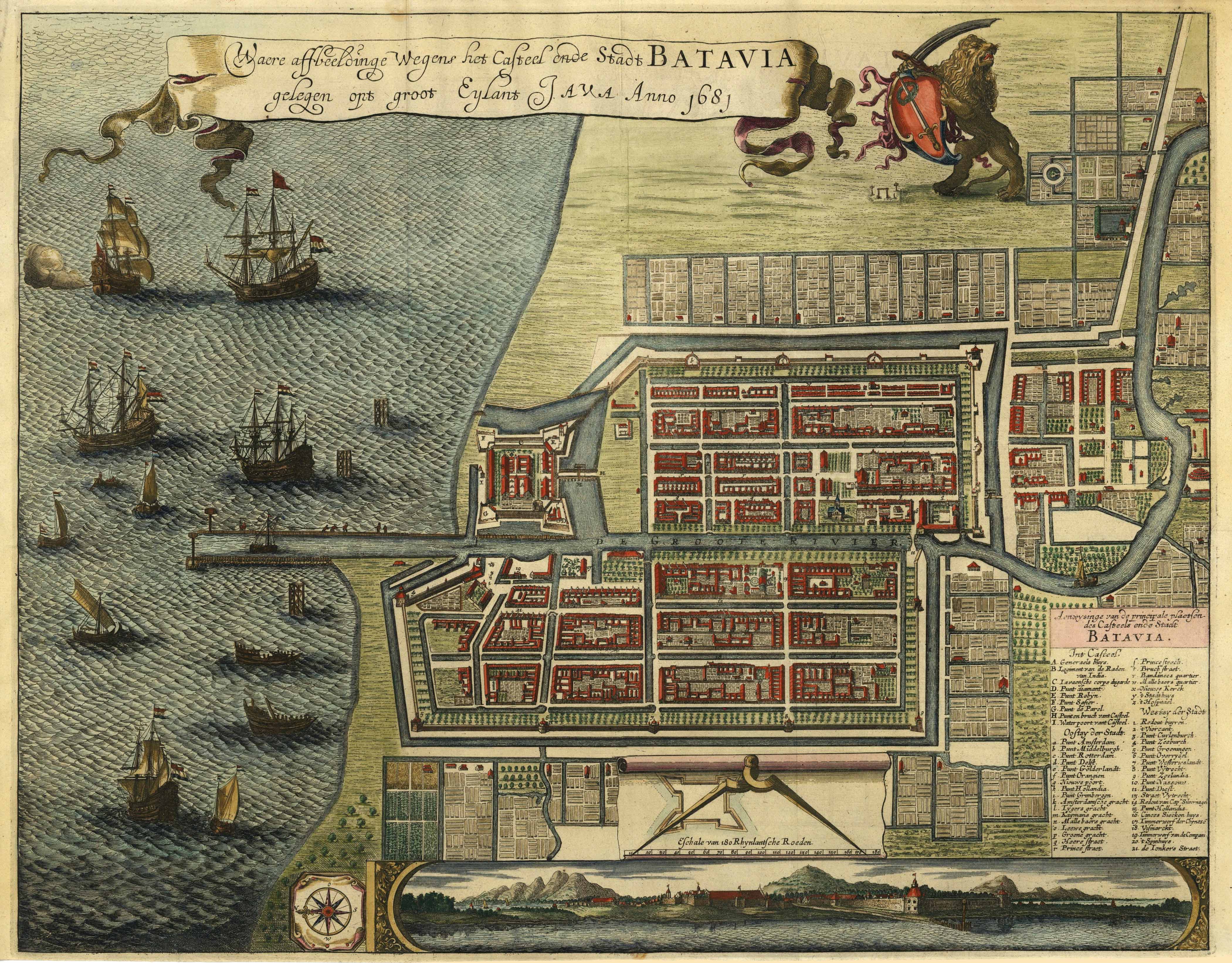

The Dutch East Indies refers to the former Dutch Colony that occupied the East Indies―present-day Indonesia―from 1800, until the armed resistance of the Indonesian National Revolution in 1945. Early occupation of the region began on March 20, 1602 by the Dutch East India Trading Company; it was not until 1800 that the area was officially taken over by the Dutch government and nationalized.

In 1916, eugenicist Madison Grant wrote The Passing of the Great Race—a book which Adolf Hitler later referred to as “his bible” (Kuhl 2002, 85). In it, Grant mused about the future of the Dutch East Indies Colony and the lack of ethnic conquest by Whites (Grant 1922, 78). He was concerned with White men procreating in the Dutch East Indies and figured they stood little chance of overtaking the indigenous population unlike how the “Americans [had] exterminated the Indians” (Grant 1922, 78). Grant was also interested in issues surrounding heritability. He stated, “…they amalgamate and form a population of race bastards in which the lower type ultimately preponderates”(Grant 1922, 78).

Issues of heredity in the Dutch East Indies were of primary concern to eugenicists becuase “most European migrants to the Indies were men; when they arrived in the colonies they secured their social status by marrying into prominent Indo-European families” and subsequently fathering children (Pols 2014). Like Grant, eugenicists with their eye on the East Indies, worried about the long-term effects of interbreeding. They “aimed to provide a scientific approach to the many social problems…between upper-class, full-blood Europeans, Indo-Europeans, and the indigenous population…”(Pols 2014).

A Decade of Progress

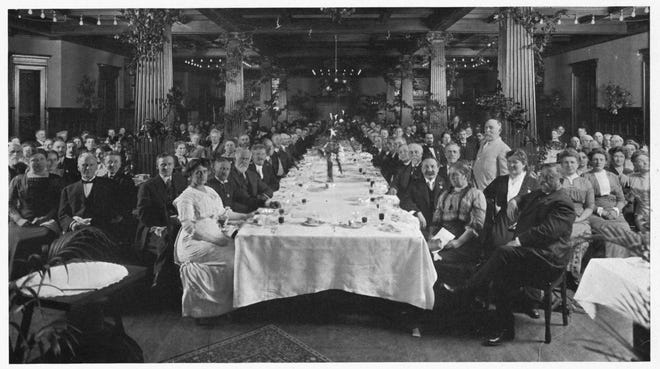

From August 21-23, 1932 The Third International Congress of Eugenics was held at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. The presidential address was delivered by Charles B. Davenport, founder of the Eugenics Records Office, who like Grant, had ties back to Nazi Germany. Davenport shared his vision for the future and his belief that social problems could be remedied with eugenic policy. At the conference he posited, “can we by eugenical studies point the way to produce the superman and the superstate?”(Davenport 1934, 17).

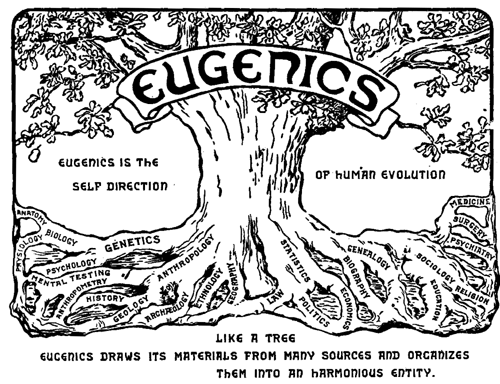

The conference resulted in a publication of scientific papers on eugenics research, known as A Decade of Progress in Eugenics, in which the authors explored eugenics research undertaken around the globe beginning in 1922. Both Madison Grant and Charles Davenport were members on the Committee of Publication.

Photo Scanned From : Harry H. Laughlin, The Second International Exhibition of Eugenics held September 22 to October 22, 1921, in connection with the Second International Congress of Eugenics in the American Museum of Natural History, New York (Baltimore: William & Wilkins Co., 1923).

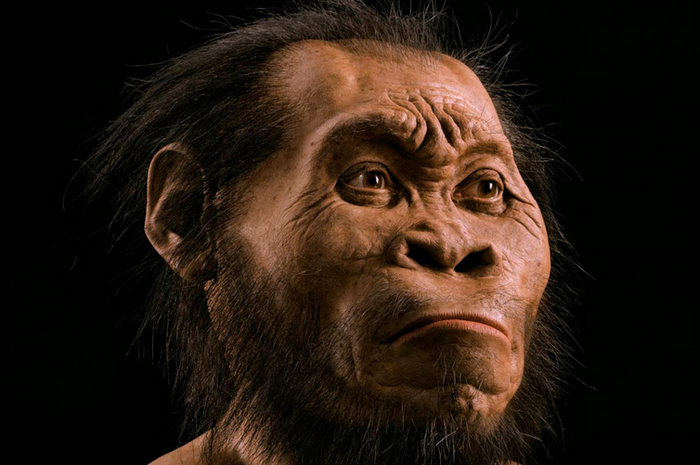

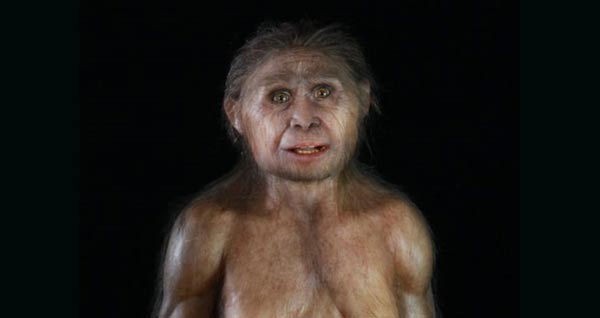

Former presiding chair of the previous Second International Congress of Eugenics, a good friend of Davenport’s and the former host of the Third conference, was Mr. Henry Fairfield Osborn. Osborn was an American paleontologist with an interest in human evolution and the president of the American Museum of Natural History ( a position he held for 25 years).

Osborn wrote prefaces for Grants The Passing of the Great Race, in which he declared “…race implies heredity and heredity implies all the moral, social and intellectual characteristics and traits which are the springs of politics and government” (Grant 1922, vii). Osborn, like many Eugenicists, worried that traits such as criminality, feeblemindedness, and pauperism were all inheritable; if left unchecked these traits would become a burden to society. He wrote, “…the true spirit of the modern eugenics movement (is)…the conservation and multiplication for our country of the best spiritual, moral, intellectual and physical forces of heredity”(Grant 1922, viii). In other words, Osborn was a proponent of selective breeding―or birth selection―to use the parlance of the times.

In a paper written for the eugenics conference, Osborn turned his attention to Java in the Dutch East Indies. He expressed concern about overpopulation, stating “… the Javanese population is mounting with an alarming rapidity, having jumped from 12,000,000 to 40,000,000 in an incredibly short space of time, a naturally fertile race being protected from disease and multiplying under their original mating customs”(Osborn 1934, 31).

In response to the perceived overpopulation problem in Java, Osborn recommended birth selection as a positive eugenic solution, writing that it both “aids and encourages the survival and multiplication of the fittest [and also acts to]…check and discourage the multiplication of the un-fittest (Osborn 1934, 29). To provide an example of the negative effects of a population unchecked, he pointed towards the United States of America and proclaimed “there are millions of people who are acting as dragnets or sheet-anchors on the progress of the ship of state” (Osborn 1934, 32).

Osborn’s writing reflects the growing trend of eugenic concerns in the Dutch East Indies towards racial differences and racial hybridity (Pols 2014). Osborn was a prominent international figure “…he was second only to Albert Einstein as the most popular and well-known scientist in America” (Regal 2002, xii). “Because of his public profile Osborn’s pronouncements on science, education and the state of society were taken as authoritative by many” (Regal 2002, xii).

Eugenics and Physical Anthropology

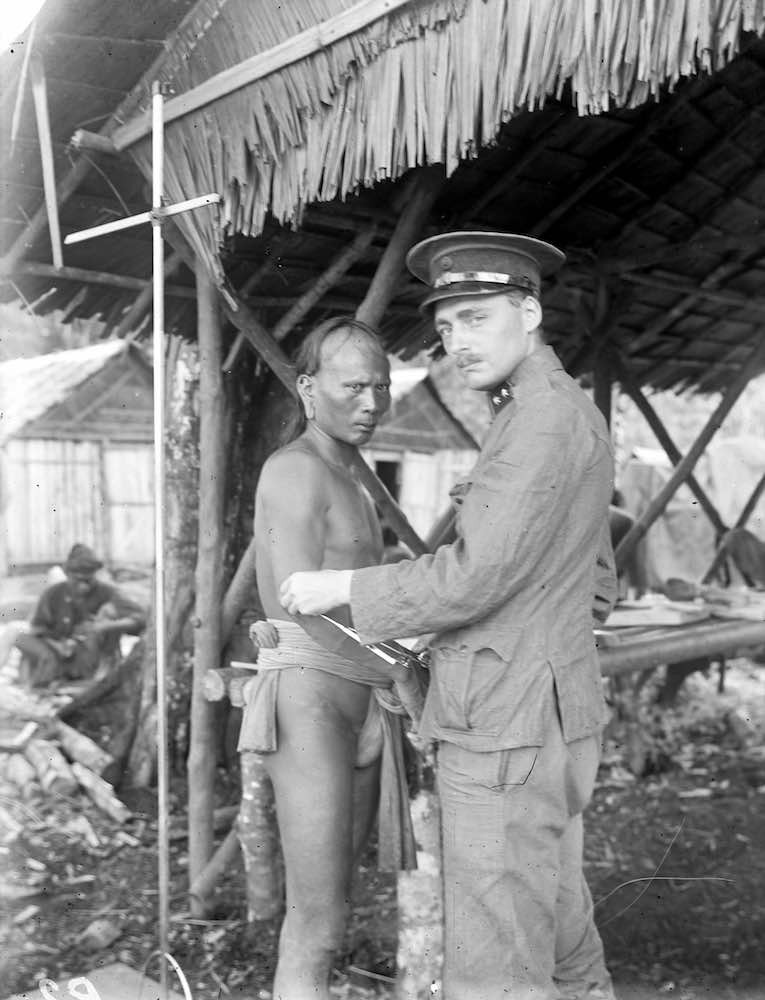

Rubbing elbows with Osborn at the Third International Eugenic Conference was H. J. T. Bijlmer, a lecturer in Physical Anthropology at the University of Amsterdam. He began his career in anthropological research in the Dutch East Indies (Sysling 2013, 113). He had used his position as a military medical inspector to obtain blood samples from indigenous people(Bijlmer 1934, 51). “He hoped that blood groups research would provide a new marker for racial classifications…”(Sysling 2013, 113). Bijlmer published an article alongside Osborn’s paper in A Decade of Progress in Eugenics where he revealed his blood sample study results. By publishing his blood sample research in the Eugenics Journal he likely hoped his research would be utilized by eugenicists in pursuing their endeavor to use racial classification to employ birth selection laws within the colony.

Furthermore, Bijlmer was willing to reshape his ideas, once back in Europe, to obtain results that pleased his cohorts (Sysling 2016, 24). He said he was willing to “use words that went against some of his anthropological findings” because his audience preferred them (Fenneke Sysling 2016, 24). Bijlmers willingness to set aside any shred of an anthropological code of ethics was part of a growing trend of ethically questionable behavior by physical anthropologists throughout the Dutch East Indies.

Bijlmer’s Predeccesor, J.P. Kleiweg de Zwaan (aka: Jo Kleiweg de Zwaan) was a Professor in anthropology and medicine for the indigenous people of the Dutch colonies at the University of Amsterdam. He, like Bijlmer, also started his career in anthropological research in the Dutch East Indies (Sysling 2013, 113). It was Zwaan who “…suggested the forming of a ‘standard committee’ on blood groups”…(Bijlmer 1934, 51) and thusly inspired Bijlmer to begin collecting blood samples.

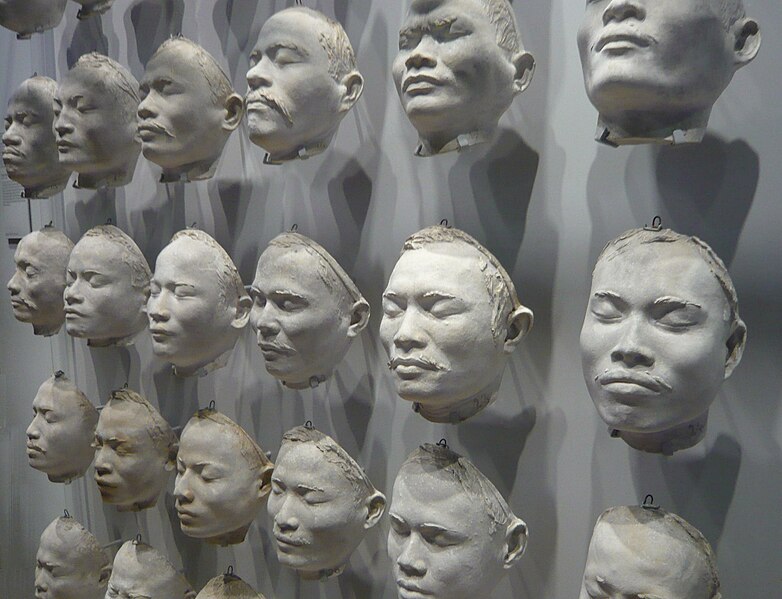

Zwaan was based out of the Colonial Museum, which is now as the Tropenmuseum (Sysling 2016, 1). For the museum, he amassed a massive collection of skulls, bones, photographs, plaster casts, and somehow human embryos preserved in spirits as well (Sysling 2016, 1).

Zwaan’s collection of plaster casts is the largest in the Netherlands and consists of 158 casts of men from the East Indies. The making of plaster casts was known to cause allergic skin reactions, fear and anxiety in the men undergoing the procedure (Sysling 2016, 90). Zwaan promised at least one villager a cure for impotence, should the man allow himself to be cast (Sysling 2016, 92). This was an ailment for which Zwaan had no such remedy.

Anthropologists, including Zwaan, purchased skulls from indigenous people. In one account Zwaan spoke of the “greediness of a Nias man” who refused to sell him a headhunted head for less than 200 Dutch Guilders (Sysling 2016, 27). According to Coinmill.com, 200 Dutch Guilders is equivalent to about 108 U.S Dollars. Adjusted for inflation that comes out to $3,378.84 in 2020. Clearly, skulls were highly valued by anthropologists.

Zwaan’s appetite became so voracious for human remains that he published a request for body parts in a Dutch Indies Journal. He appealed to “colonial administrators, military men, missionaries, doctors, planters and explorers [asking them] to send ethnological and anthropological collections to the Colonial Institute”(Sysling 2016, 40). “Entire skeletons…were preferred” (Sysling 2016, 40).

Perhaps responding to Zwaans call for body parts, J.F.K. Hansen, an officer in the Dutch army and armchair anthropologist, paid two Christian Batak missionaries to steal human skulls from a graveyard, disguise them as coconuts, and forward them to the Colonial Institute (Sysling 2016, 41).

Unfortunately, these unethical means for gathering evidence that could be used to define racial categories were not isolated incidents. Physical Anthropologists in the Dutch East Indies often made payments, performed acts of coercion, offered medical aid and used intimidation tactics to collect data—blood samples, skulls, body parts or body measurements (Sysling 2016, 48). Recognizing the uneven power balance tipped in their favor as members of the colonial regime, they were not afraid to take advantage of those in subjugation whenever possible (Sysling 2016, 72). They routinely profited from Colonial violence by obtaining body parts after colonial subjects were killed by the death penalty or in war (Sysling 2016, 11). If disturbing and violent means of data collection were the norm for Physical Anthropologists, then studies like Bijlmer’s blood research, Zwaans collection of embryos or studies by G.Vrlock & T. Zaayer on the female pelvises’ of living Javanese women, take on a particularly frightening quality (Kleiweg De Zwaan 1923, 4-5).

It also forces us to consider what the motivation could have been for this level of obsessive dedication? What was it that Physical Anthropologists were trying to achieve?

Eugenics―the Undeclared Motivation

“Eugenics is the study of the agencies under social control that may improve of impair the racial qualities of future generations either physically or mentally.”

Sir Francis Galton – Published in A Decade of Progress in Eugenics, 1932.

There were numerous ties between the colonial regime and eugenics in the Dutch East Indies. For example, “in 1927, the Eugenics Association of the Dutch East Indies (Eugenetische Vereeniging in Nederlansch-Indië) was founded in Batavia”, the capital of the Dutch East Indies(Pols 2014). Furthermore, “The first Dutch periodical exclusively devoted to eugenics, Ons Nageslacht (Our Progeny)” began to be published in 1928, also in Batavia (Pols 2014).

Zwaan, however, is not often linked to eugenics. Zwaan’s Wikipedia page, for example, is devoid of any mention of eugenics and yet Zwaan’s student Bijlmer was a known eugenicist with ties to Madison Grant, Charles Davenport and Henry Fairfield Osborn. All three of these men had ties to Hitler and Nazi Germany as well. Additionally, Zwaan’s direct supervisor Lodewijk Bolk was a Dutch anatomist who “talked about race in terms of decline and fall, disease and restoration, emphasizing the connection between physical and mental characteristics and [most importantly]the eugenic uses of anthropological knowledge”( Sysling 2016, 125).

Furthermore, Zwaan was a founder of the National Bureau for Anthropology/Ethnology (Neatherlands) in 1922. “One of the main endeavors of the Bureau from 1925 onward was to publish a journal called, Mensch en Maatschappij (Man and Society) that included articles on a wide range of subjects including many on heredity and eugenics” (Sysling 2016, 19). Zwaan was firmly situated at the center of a professional circle ensconced by eugenicists. Many scholars have chosen to ignore the numerous ties that Zwaan (and his colleagues) had to eugenics. They dismiss his associations as merely a coincidence of the time period, however, it must be noted that in the 1930’s, Zwaan like his supervisor before him, “added eugenics as one of the applications of physical anthropology…” in his writing (Sysling 2016, 136).

Why define Race?

Zwaan and many others like him collected body parts, blood samples, plaster casts and other objects which fill museum shelves and display cases throughout the word. At the time, however, they were used to promulgate racial categories. Although, attempts to define race within the East indies failed over and over, Physical Anthropologists continued to collect “data” in an attempt to find any shred of evidence they could use to establish alterity. These categories were a necessary platform for anyone wanting to pursue eugenic ideology given that it is not possible to have racial cleansing or birth selection without them.

Considering the amount of eugenic ideology that entrenched Zwaan and his cohorts it is likely that many of them were eugenicists. At the very least it probable that they were heavily influenced by eugenics. These eugenic influences may explain why they willing to go to such great lengths to define racial categories to establish alterity between the autochthonous people of Indonesia and members of the Dutch State, as well as its European allies.

References:

H.J.T. Bijlmer. 1934. “Bloodgroups in Relation to Race in the Dutch East Indies.” In A Decade of Progress in Eugenics, 51–53. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins Co.

Charles B. Davenport. 1934. “Presidential Address: The Development of Eugenics.” In A Decade of Progress in Eugenics, 17–22. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins Co.

Grant, Madison. 1922. The Passing of the Great Race : Or the Racial Basis of European History. New York: Scribner’s Sons. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uiug.30112004957228&view=1up&seq=7.

Kleiweg de Zwaan, J. P. (1875) 1923. Physical Anthropology in the Indian Archipelago and Adjacent Regions. Y J. H. de Bussy. J. H. de Bussy. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015032644596.

Kuhl, Stefan. 2002. Nazi Connection: Eugenics, American Racism, and German National Solcialism. Oxford University Press. https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.libproxy.berkeley.edu/lib/berkeley-ebooks/reader.action?docID=431024.

Henry Fairfield Osborn. 1934. “Birth Selection versus Birth Control.” In A Decade of Progress in Eugenics, 29–41. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins Co.

Pols, H. 2014. “Indonesia (Former Dutch East Indies).” The Eugenics Archives. October 31, 2014. http://eugenicsarchive.ca/discover/world/5454098bc5159e4c76000001.

Regal, Brian. 2002. Henry Fairfield Osborn : Race, and the Search for the Origins of Man. Aldershot, Hants, England ; Burlington, Vt: Ashgate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/327391393_Henry_Fairfield_Osborn_Race_and_the_Search_for_the_Origins_of_Man/link/5ee20685458515814a5468ba/download.

Sysling, Fenneke. 2013. “Geographies of Difference: Dutch Physical Anthropology in the Colonies and the Netherlands, ca. 1900-1940.” BMGN – Low Countries Historical Review 128 (1): 105–26. https://doi.org/10.18352/bmgn-lchr.8357.

Fenneke Sysling. 2016. Racial Science and Human Diversity in Colonial Indonesia. Singapore Nus Press.

Additional Content:

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/54/a8/54a8257b-aa4b-411f-831e-8248be876b14/joordens_trinil_engravedshelledit.jpg)